Quick Look

Grade Level: 4 (3-5)

Time Required: 45 minutes

Lesson Dependency: None

Summary

Students begin to make sense of the phenomenon of electricity through learning about circuits. Students use the disciplinary core idea of using evidence to construct an explanation as they learn that charge movement through a circuit depends on the resistance and arrangement of the circuit components. Students also explore the disciplinary core ideas and crosscutting concepts of energy and energy transfer in the context of energy from a battery. In one associated hands-on activity, students build and investigate the characteristics of series circuits. In another activity, students design and build flashlights.Engineering Connection

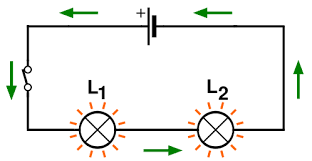

The circuit diagram is the language of electrical design and engineering. These diagrams are maps that anyone can read to see how to build the circuit. When engineers design or build any electrical circuit they either create a new circuit diagram or use an existing one. Interpreting circuit diagrams is an essential skill for electrical and many other types of engineer. Once built, these electrical circuits are used to light our houses, power computers, run cars, and pretty much every modern device that uses electricity.

Learning Objectives

After this lesson, students should be able to:

- Describe how current changes in a series circuit when a light bulb or battery is added or removed from the circuit

- Understand that chemical energy in a battery is converted to electrical energy in a circuit, which is converted to thermal energy and light in a light bulb. Also, sound energy can be produced from electricity, by way of a moving speaker cone. For this example, electricity is converted to mechanical motion (to move the speaker), which then produces sound energy in the form of moving waves of air.

- Describe the connections among representations of circuit symbols.

- Find the voltage of batteries connected in series by summing the individual batteries' voltages.

Pre-Req Knowledge

Battery, simple circuit, current electricity, resistance, voltage, current

Introduction/Motivation

Ask students if they ever had an electronic game or toy that required batteries? (Many will answer yes.) Ask how many batteries the game or toy needed? (Possible answers: One, two, three or four batteries.) Ask students to brainstorm why some electronic games or toys require more batteries than other games or toys? (Possible answers: Some toys need more power, some games need more electricity.) Three AA batteries connected "in series" can provide more voltage than a single AA battery. This is because the chemical energy in a battery gets converted to electrical energy in a circuit, and there is more chemical energy available in a circuit with three AA batteries “in series” than in a circuit with only a single AA battery. Electrical circuits as well as batteries can be "in series" or "in parallel." During today's lesson we will learn what "in series" and "in parallel" mean.

How do electrical engineers know how many batteries are needed to operate an electronic game or toy? One way that they can determine the necessary voltage and current is to create a map of the circuit. Electrical engineers can use a map, or circuit diagram, to determine how much power a device needs to operate.

Ask students why some devices use batteries and other devices use a wall outlet for power? (Answer: Batteries produce a different type of current than a wall outlet.) The current that comes from a battery is called direct current (DC). The current that comes from a wall outlet in our homes or schools is called alternating current (AC). Explain to students that many televisions, computers, DVD players and stereos have hardware (equipment) inside the device that converts the alternating current (AC) to direct current (DC) for operation of the device.

Lesson Background and Concepts for Teachers

What Are Circuit Diagrams?

Circuit diagrams are graphical representations of circuits or electrical devices. Each component of a circuit has a corresponding standard symbol (see Figure 2). When drawn, these symbols are linked together to show the construction of a circuit; the resulting diagram is a map that anyone can read to see how to build the circuit. In effect, the circuit diagram is the language of electrical design and engineering. When engineers design or build any electrical circuit they either create or use an existing circuit diagram. Interpreting circuit diagrams is an essential skill for electrical engineers and many other types of engineers.

Wires, which have a very low resistance, are represented by straight or angular lines connecting electrical components. A resistor is a device used to regulate the amount of current in a circuit. There are many different resistors, with resistances ranging from a few ohms to millions of ohms. The resistor is symbolized by a zigzag line. There are various ways to represent a light bulb in a circuit. In this unit, the symbol used for a light bulb is the circle with an "x", as shown in Figure 2. A cell, or electrochemical cell, is represented by two lines of different lengths, positioned perpendicular to the wire line, to show that there is a voltage between the positive and negative terminals; the shorter line is the negative terminal of the battery. A battery is composed of multiple cells. Notice the symbol for a battery appears to look like two cells in a row, or in series. The symbol for a switch shows that the electrical connection can be open and closed at the contact.

To draw a circuit diagram of an existing series circuit, draw the layout of the circuit and corresponding symbol as you encounter each circuit element. Although wires in a circuit are usually curved, draw wires in the circuit diagram as either straight lines or angular, bent lines.

How Are Electrical Elements Connected in a Circuit?

There are many components that may be used in circuits: batteries, light bulbs, wire and switches. The parts of a circuit can be connected in two different ways. When they are connected such that there is a single conducting path between them, they are said to be connected in series. The circuit on the left in Figure 3 shows two resistors in series. When circuit elements are connected across common points such that there is more than one conducting path through the circuit, they are connected in parallel. The circuit on the right in Figure 3 shows two resistors in parallel. Refer to the Bulbs & Batteries in a Row activity to have students practice building their own circuits with several components. A typical electrical device is composed of many smaller series and parallel portions. In general, only very simple circuits can be entirely in series.

Ohm's Law and Series Circuits

Ohm's Law is a fundamental mathematical equation describing the relationship between voltage, current and resistance. In fact, Ohm's Law defines resistance: R = V/I, where R = the resistance of a circuit element, V = total voltage supplied to the circuit by a power source (a battery, for example), and I = current through the circuit. The equation can be rearranged (V=I*R) to predict a voltage drop across a circuit element with a known resistance and a known current pass through. The voltage supplied to the circuit, V, and the total voltage drop throughout the circuit VT must be equal and opposite. This means V + VT = 0. The total voltage drop through the circuit is equal to: I*RT = VT, where RT is the total resistance in the circuit. We will explore how to find the total resistance, RT, in this lesson for series circuits and in the upcoming lesson and activities in this unit for circuits with elements in parallel.

A series circuit and its matching circuit diagram are shown in Figure 4. Because there is only one path for charge movement through the circuit, the current is the same throughout the circuit. As electrons move through the circuit, their flow is resisted by each light bulb, such that the total resistance to charge movement is the sum of all the resistances in the path. From Ohm's law (written in the form I=V/R), we know that the total current is equal to the voltage divided by the total resistance. There is a voltage drop across each bulb. The sum of the voltage drops is equal to the voltage of the power source, which in this case is a battery. Because the current is the same throughout a series circuit, the voltage drop across each light bulb is directly proportional to that bulb's resistance (by rearranging the Ohm's law equation, V=I*R).

When batteries are linked in series, the total voltage is the sum of the voltages of each battery. So, if we make a circuit with three 1.5 V batteries in series as the voltage source, the total voltage is 4.5 V, as shown in Figure 5. This is how battery manufacturers make batteries with higher voltages; they just link several batteries (of the same potential) together in series.

What Is the Difference between DC and AC?

Direct current, or DC, refers to the movement of charge in a circuit in one direction only. Batteries, photovoltaic cells and some generators provide direct current. For example, in a battery-powered flashlight, electrons leave the negative terminal of the battery and move through the flashlight circuit to the positive terminal. Have students build their own flashlight with the Light Your Way: Design-Build a Series Circuit Flashlight activity. Many everyday portable devices operate on direct current. Have students apply their knowledge of such devices to design and build their own toy in the Build a Toy Workshop activity.

In AC, or alternating current, electrons are moved back and forth in a circuit. Because of this, the electrons only move a small distance around a relatively fixed position in the circuit. Although AC and DC generators are similar, AC has been proven to be a more effective way to transmit electrical power. Whenever you plug an electrical device into a wall socket you are using AC current. The current direction alternates because the direction of voltage is alternated at the power plant. In the U.S., we use current that changes direction 60 times a second, called 60-hertz current.

Lesson Closure

On the classroom board, draw an example series circuit that includes several components (for example, see Figure 4). Qualitatively, compare the current and voltage in different parts of the circuit. Ask the students to compare the current in three bulbs of increasing resistance connected in a series arrangement. (Answer: Current is the same everywhere throughout a series circuit.) Next, compare the voltage across each of these three bulbs. (Answer: The voltage drops when it encounters the resistance of a light bulb, so the first light bulb would have the most voltage and each consecutive light bulb would experience less voltage.) What happens to the total voltage when batteries are connected in series? (Answer: The total voltage is the sum of each battery's voltage.)

Vocabulary/Definitions

alternating current: An electric current that reverses direction at regular intervals. Abbreviated as AC.

circuit diagram: A graphical representation of a circuit, using standard symbols to represent each circuit component.

direct current: An electric current in one direction only. Abbreviated as DC.

energy transfer: The movement of energy within a system. Can include the transformation of one type of energy to another (with some loss). Relevant examples include electricity to motion (fan), electricity to light and heat (light bulb), and electricity to sound and motion (sound system).

load: A device or the resistance of a device to which electricity is delivered.

parallel circuit: An electric circuit providing more than one conducting path.

resistor: A device used to control current in an electric circuit by providing resistance.

series circuit: An electric circuit providing a single conducting path such that current passes through each element in turn without branching.

Assessment

Pre-Lesson Assessment

Discussion Question: Solicit, integrate and summarize student responses:

- Why do some devices use batteries and other devices use a wall outlet for power? (Answer: Batteries produce a different type of current [DC] than a wall outlet [AC])

Post-Introduction Assessment

Voting: Ask a true/false question and have students vote by holding thumbs up for true and thumbs down for false. Count the votes and write the totals on the board. Give the right answer.

- True or False: Three AA batteries connected "in series" provide more voltage than a single AA battery. (Answer: True.)

- True or False: Batteries can be "in series" or "in parallel." (Answer: True.)

- True or False: Electrical engineers use a circuit diagram to determine how much power a device needs to operate. (Answer: True.)

- True or False: Batteries produce the same type of current as a wall outlet. (Answer: False. Batteries produce a different type of current [DC] than a wall outlet [AC].)

- True or False: The current that comes from a battery is called alternating current. (Answer: False. The current that comes out of a wall outlet in our homes or schools is called alternating current [AC]. Batteries are direct current [DC].)

- True or False: (Sound energy can be produced from electricity or by smacking your desk? Answer: True, electrical sources such as batteries can power small speakers and your hand can produce sound waves from hitting the hard surface of the desk.)

Lesson Summary Assessment

Quick Survey: Give students a piece of paper and ask them to write down the answers to the following three questions.

- What did you like best about the lesson?

- What could be done better?

- What did you learn that you didn't know before?

Numbered Heads: Have the students on each team pick numbers (or number off), so each member has a different number. Ask the students the questions below (give them a time frame for solving it, if desired). The members of each team should work together on the question. Everyone on the team must know the answer. Call a number at random. Students with that number should raise their hands to answer the question. If not all the students with that number raise their hands, allow the teams to work a little longer. Ask the students:

- If you remove one bulb from a series circuit with three bulbs, the circuit becomes a(n) _________ circuit. Open or closed? (Answer: Open.)

- What happens to the other bulbs in a series circuit if one bulb burns out? (Answer: They all go out.)

- When more bulbs are added to a series circuit, each lamp becomes _____________. Brighter or dimmer? (Answer: Dimmer.)

- When batteries are connected in series, the voltage across them ____________. Increases, decreases or stays the same? (Answer: Increases.)

- Draw a circuit diagram of a series circuit with two batteries and three light bulbs. (Answer: It should look like Figure 4 with the switch replaced with a second battery.)

Figure Drawing Race: Write the circuit symbols on the board. Divide the class into teams of four, having each team member number off so each has a different number, one through four. Call a number and have students with that number race to the board to draw the correct circuit diagram. Give a point to the team whose teammate first finishes the drawing correctly. Ask the students to draw circuit diagrams of the following:

- A series circuit with one battery and two light bulbs

- A series circuit with two batteries, one light bulb and one switch

- A series circuit with one battery, one light bulb, and one resistor

- A series circuit with three batteries, two light bulbs, and two resistors

- A series circuit with one battery, two resistors, two light bulbs and one switch

- A series circuit with three batteries, four light bulbs and one switch

- A series circuit with one battery, and three each alternating bulbs and resistors and one switch

Homework/Independent Practice:

- Have the students count the number of transformers in their homes. See the Lesson Extension Activities section for more information on transformers.

Lesson Extension Activities

Research the history and development of the flashlight. The Flashlight Museum has many photographs of antique flashlights and portable light devices, at: http://www.flashlightmuseum.com/.

Learn about transformers: A transformer is an electrical device used to convert AC power at a certain voltage level to AC power at a different voltage, but at the same frequency. A considerable amount of power is lost in transmitting energy along a power distribution grid. Additional energy is consumed in transformers at substations. Many everyday consumer electronic devices require transformers that are always on and consuming power, even if no one is using the electrical device.

- Have students count the number of transformers they have at home. Transformers may be attached to computers, printers, scanners, speakers, answering machines, cordless phones, mobile phone chargers, electric screwdrivers, electric drills, baby monitors, modems and camcorders. Transformers are not always easy to recognize; obvious transformers look like larger boxes (usually the same color as the cord) attached to the end of the cords at the point where you plug the device into the electrical outlet.

- If you touch a transformer and it is warm, you are feeling (wasted) electrical energy turned to heat energy. Have the students calculate the amount of energy wasted each year by the transformers in their house. The power consumption is not large — on the order of 1 to 5 watts per transformer, but it does add up. Say you have five transformers, each consuming 5 watts each. That means that 25 watts are being wasted constantly. If a kilowatt-hour costs 10 cents in your area, that means you are spending 10 cents every 1,000 watt-hours/25 watts = 40 hours. There are 8,760 hours in a year, so 8,760 hours/40 hours = $21.90 every year.

- Have the students calculate the total amount of energy wasted by transformers in the entire country. There are 100 million households in America. If each household wastes 25 watts on these transformers, that is 2.5 billion watts. At 10 cents a kilowatt-hour, that is 2,500,000,000 watts/1000 watts or $250,000 every hour. That is $2,190,000,000 ($2 billion) wasted every year.

Subscribe

Get the inside scoop on all things TeachEngineering such as new site features, curriculum updates, video releases, and more by signing up for our newsletter!References

Berg, Eric. Mechanical Engineering Senior, Colorado School of Mines, "How Does a Transformer Work?" http://www.physlink.com/ Accessed April 28, 2004.

Hewitt, Paul G. Conceptual Physics. 8th Edition. New York, NY: Addison Publishing Co., 1998. Raloff, Janet. "Must we pull the plug?" Science News. October 25, 1997.

Ropeik, David. MSNBC – How the Grid Powers a Continent. January 23, 2001. MSNBC News. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/3077316/ns/technology_and_science-science/t/how-grid-powers-continent/#.T4M6w_WfzTo Accessed April 7, 2004.

Schneider, Stuart. Flashlight Museum. Wordcraft.net. Accessed April 7, 2004.

Silberman, Steve. Wired News: Girding Up for the Power Grid. June 14, 2001. Wired Magazine. www.wired.com Accessed April 7, 2004.

Copyright

© 2004 by Regents of the University of ColoradoContributors

Xochitl Zamora Thompson; Sabre Duren; Joe Friedrichsen; Daria Kotys-Schwartz; Malinda Schaefer Zarske; Denise W. Carlson; Carleigh SamsonSupporting Program

Integrated Teaching and Learning Program, College of Engineering, University of Colorado BoulderAcknowledgements

The contents of this digital library curriculum were developed under grants from the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE), U.S. Department of Education and National Science Foundation (GK-12 grant no. 0338326). However, these contents do not necessarily represent the policies of the Department of Education or National Science Foundation, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Last modified: December 12, 2023

User Comments & Tips